- Home

- О компании

- История компании

История компании

Полная история появления и развития компании Нестле. Узнайте подробно в чем секрет успеха Nestle. Интересные факты и достижения

Вкусные завтраки «Несквик», шоколадки «КитКат», растворимый Кофе «Нескафе», бульонные кубики «Магги», мороженое «Максибон», капсулы для кофемашин «Неспрессо», минеральная вода «Виттель», холодный чай «Нести», корма для питомцев «Пурина» и «ПроПлан». Все это — великий и могучий концерн Nestlé, который за полуторавековую историю успел объединить под своим началом более 2000 производителей продуктов питания. Команда Бизнес-журнала lindeal.com предлагает вам проследить, как маленькая компания немецкого фармацевта Анри Нестле превратилась за 150 лет в настоящего гиганта, крупнейшего производителя продовольствия на планете.

Nestlé: что это такое? (краткая справка о компании)

Nestlé Société Anonyme — швейцарская транснациональная корпорация, крупнейший в мире производитель продуктов питания:

- Дата основания: 1866.

- Основатели: Анри Нестле, Джордж и Чарльз Пейдж.

- Руководители: председатель совета директоров Пол Бюльке, СЕО Ульф Марк Шнайдер.

- Число сотрудников: 276 000.

- Дочерние предприятия: Nestea, Vittel, Bonka, Nestle Waters, Alcon, Nestle (United States, Canada, Rossiya, España, India), Orion, Осем, Froneri, Nestlé Česko, BlueTriton Brands, Nespresso, Nestlé Deutschland, Hjem-IS, Deutsche Aktiengesellschaft für Nestle-Erzeugnisse, Rowntree’s.

Акционерная компания «Нестле» известна своими брендами «КитКат», «Магги», «Несквик», «Нескафе», «Нести». В настоящее время производит детское и лечебное питание, молочную продукцию, растворимый кофе, специи и бульоны, мороженое и шоколад, холодный чай и минеральную воду, косметику и фармацевтическую продукцию, замороженные блюда и готовые завтраки, а также корма для домашних животных.

Летопись «Нестле» с 1866 года по сегодняшний день

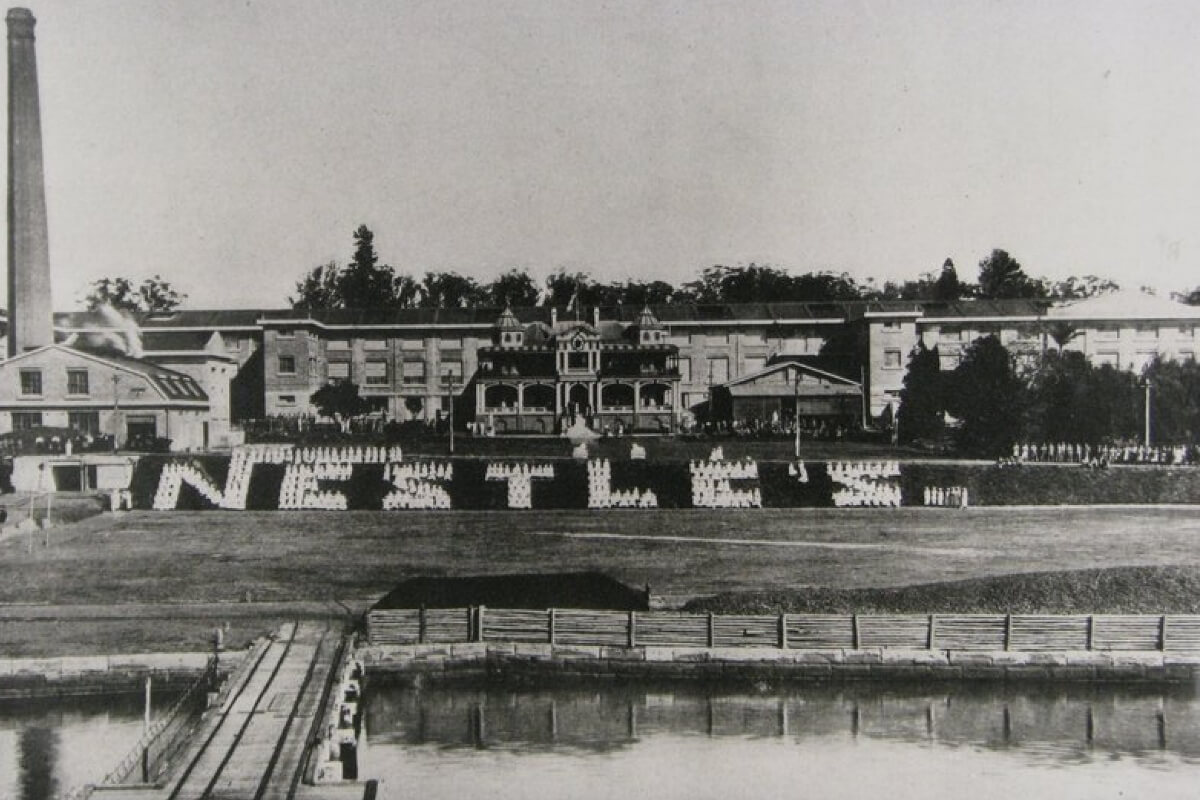

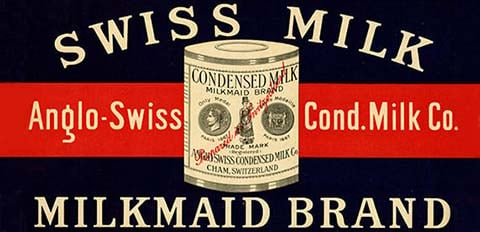

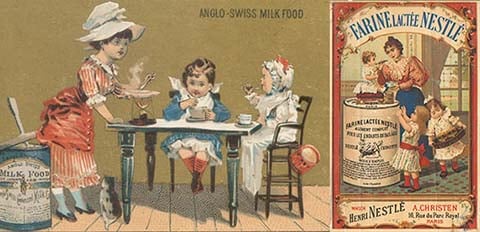

История современного продуктового гиганта Nestlé началась в 1866 в Швейцарии, в местечке Шам: в тот год «Англо-Швейцарская компания» запустила первую в Старом Свете фабрику по производству сгущенного молока. Ее основатели, братья-американцы Джордж и Чарльз Пейдж, использовали собственный опыт, накопленный в Штатах. Европейская горная страна, славящаяся своим альпийским молоком, стала идеальным местом для производства. Наладив процесс, предприниматели начали поставлять свою продукцию в крупные города Европы под брендом Milkmaid — вкусная, безвредная и долго хранящаяся альтернатива обычному молоку.

1866-1905: создаем свои ценности

Уже год спустя после открытия события стали быстро развиваться:

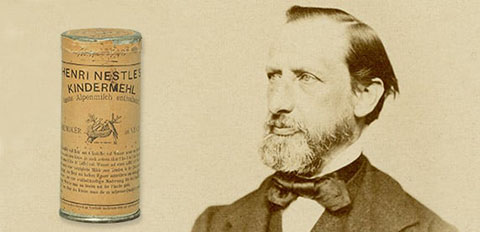

- 1867: германский фармацевт Анри Нестле основал свою фабрику — налаживает Производство «молочной муки» Farine Lactée в швейцарском городе Веве. Ученый обратился к разработке смеси из коровьего молока, сахара и пшеничной муки, чтобы снизить смертность среди малышей, которые не могли быть вскормлены натуральным грудным молоком. Именно тогда разработчик начал впервые использовать знакомый нам логотип с птенцами и гнездом.

- 1875: Анри продает свою фабрику профессиональным бизнесменам, способным качественно увеличить объемы производства и продаж.

- 1878: начало ожесточенной конкуренцией между «Англо-Швейцарской компанией» и «Нестле», поставляющими на рынок аналогичные продукты — детские смеси и сгущенку.

- 1904: купив право на Экспорт продуктовых изделий Peter & Kohler, Nestlé запускает торговлю шоколадом. В это же время Анри Нестле разрабатывает авторский рецепт молочного шоколада, который совсем скоро оценивается как коммерчески успешный продукт.

В 1905 предприятие Анри Нестле объединилось с «Англо-Швейцарской Компанией», чтобы образовать совместный концерн. И тому было самое время: городское население увеличивается, пароходное и железнодорожное сообщение усиленно развивается, что позволило снизить цены на товары широкого потребления и открыть новые возможности для транснациональной торговли.

1905-1913: вступаем в прекрасную эпоху

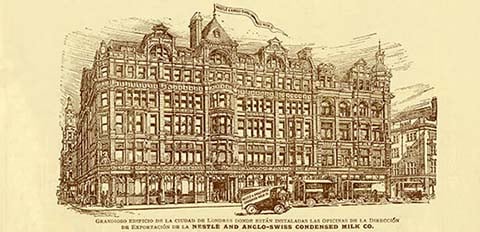

Объединенное предприятие «Нестле», обладая 20 продуктовыми фабриками, начинает расширение в Азию, Австралию, Африку и Южную Америку посредством зарубежных дочерних предприятий. Это позволяет концерну до начала Первой Мировой войны удерживать статус крупнейшего мирового производителя молочных продуктов. Nestlé & Anglo-Swiss Milk Company располагало двумя штаб-квартирами, в Шаме и Веве, к которым вскорости присоединился третий центральный офис — в Лондоне. Целью английского отделения было увеличение экспортных поставок. Параллельно расширяется ассортимент бренда, который уже включает сгущенку без содержания сахара и стерилизованное молоко.

1914-1918: сквозь тяжкие годы Первой Мировой

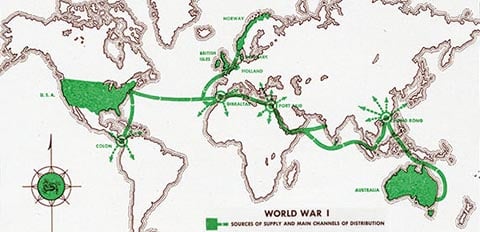

С началом военных действий спрос на шоколадные изделия и сгущенное молоко существенно возрос, однако нехватка необходимого сырья, ограничения на международные торговые операции негативно сказались на производственных масштабах Nestlé & Anglo-Swiss.

- 1914: в связи с началом войны «Нестле» получает государственные заказы на свою продукцию.

- 1915: консервированное сгущенное молоко Nestlé включено в «неприкосновенный запас продовольствия» для солдат британской армии, что ведет за собой бешеный спрос на продукт.

- 1916: приобретение норвежской торговой фабрики Ergon, обладательницы патента на оригинальное производство молочного порошка.

Чтобы решить проблему с дефицитом производства, торговая марка активно скупает производственные объекты в Австралии и Соединенных Штатах — так, к концу войны на «Нестле» работает уже 40 фабрик.

1919-1938: от кризиса — к новым возможностям

После завершения Первой Мировой спрос на консервированное молоко резко падает, что приводит в 1921 к серьезному кризису и убыткам в объединенной компании. Только-только «Нестле» удается оправиться, как новая сложная проблема — катастрофическое падение курса акций на Нью-Йоркской Бирже (1929).

- 1929: приобретение крупнейшего швейцарского производителя шоколада Peter-Cailler-Kohler, создавшего первый в стране шоколадный бренд «Кейлер».

- 1934: выпуск для австралийских покупателей солодово-шоколадного напитка Milo.

- 1934: начало производства цельномолочного порошка для грудных детей Pelargon, обогащенного кисломолочными бактериями для лучшего усвоения.

- 1936: презентация интересной новинки — белого шоколада Galak.

- 1936: ввиду увлечения мирового сообщества витаминами, «Нестле» производит собственные витаминные добавки Nestrovit.

- 1937: свежая новинка — пористая шоколадка с медовой начинкой Rayon.

- 1938: запуск одного из самых популярных продуктов компании — растворимого кофе Nescafé. Чтобы насладиться натуральным кофейным вкусом, нужно было лишь разбавить порошок горячей водой — просто настоящая диковинка для своего времени! «Нескафе» стал результатом 9-летней кропотливой работы химика Макса Моргенталера.

Но вместе с проблемами появились и новые достижения, путь возможностей: повышение профессионализма руководящего звена, централизация научной и исследовательской работы, выход новых продуктов, полюбившихся потребителям, — среди них был и кофе «Нескафе».

1939-1947: «под натиском бури»

Несмотря на то, что события Второй Мировой войны больно ударили по всем мировым производителям, «Нестле» удалось «выдержать натиск бури» — исправно снабжать своей продукцией как армию, так и гражданское население.

- 1939: опасаясь оккупации Швейцарии, бренд перебрасывает основные силы в новый штаб-офис в Стэмфорде (Соединенные Штаты). Параллельно увеличивается производство в Южной Америке, расширяются закупки сырья в Австралии и США для поставок в Африку и Азию.

- 1942-1945: продукты «Нестле» становятся популярными у американских военных, а в 1945 включаются в состав гуманитарной помощи, отправленной населению Японии и европейских стран.

- 1947: объединение со швейцарским производителем бульонов и приправ Alimentana, выпускающим свою продукцию под брендом Maggi. Название дано по имени Юлиуса Магги, разработавшего в 1884 формулу обогащенного протеином порошкового супа.

Именно в этот период концерн получил новый нейм Nestlé Alimentana и пополнил свой ассортимент специями и быстрыми супчиками «Магги».

1948-1959: все для вас!

Так как послевоенный период истории отличался постепенным ростом благосостояния населения, европейцы и американцы не скупились на удобную бытовую технику — холодильники и морозильные камеры. А значит, могли заинтересоваться замороженными продуктами — полуфабрикатами и блюдами быстрого приготовления.

- 1948: первый выпуск универсального быстрорастворимого напитка, чая Nestea, который оставался бодрящим и вкусным как в горячем, так и в охлажденном виде.

- 1948: презентация на американском рынке быстрорастворимого какао Nesquik, которое можно было с успехом развести даже в холодном молоке! Неудивительно, что новинка выбилась в лидеры продаж.

- 1948: еще одним популярным продуктом стала детская каша быстрого приготовления, которая в 1954 претерпела ребрендинг и предстала уже под известным нам названием Cerelac.

- 1954: открыли производство универсальной порошковой приправы Fondor в удобной практичной баночке с отверстиями — специю можно было применять как для готовых блюд, так и в кулинарном процессе.

- 1957: выпуск качественно нового для рынка продукта — консервированных равиоли «Магги». Они были с таким восторгом приняты публикой, что «Нестле» занялась расширенной разработкой и запуском консервированных обедов быстрого приготовления.

Эпоха пятидесятых-шестидесятых — «золотое время» для готовых напитков и блюд по типу «Магги» или «Несквик».

1960-1980: время расти и расширяться

На этом периоде развития корпорация активно практикует слияния, приобретает новые активы в самых перспективных и динамично развивающихся сегментах продуктового рынка. Вместе с расширением ассортимента кофейной, консервированной, молочной и замороженной продукции, компания выходит в совершенно новые для себя сферы — косметическую и лекарственную.

- 1960: воспользовавшись повсеместно увеличивающимся спросом на мороженое (связанным с широким распространением холодильников) «Нестле» покупает сразу двух производителей ледяного лакомства — Jopa (Германия) и Heudebert-Gervais (Франция).

- 1960: покупка производителя замороженных блюд Crosse & Blackwell.

- 1962: приобретение еще одной фабрики мороженого, Frisco (Швейцария).

- 1962: покупка торговой марки замороженных продуктов Findus (бывший владелец — шведская компания Marabou), которая с 1945 являлась одной из самых успешных в своей отрасли.

- 1968: «Нестле» ловит новую глобальную моду на увлечение молочными охлажденными продуктами. Концерн приобретает производителя йогуртов Chambourcy (Франция).

- 1969: расширение в сферу минеральной воды приобретением доли в капитале Vittel (Франция).

- 1970: запуск новой йогуртной линейки Sveltesse специально для тех, кто заботился о фигуре и правильном питании.

- 1973: приобретение американского производителя замороженных продуктов Stouffer Corporation.

- 1974: «Нестле» становится «миноритарным акционером» крупнейшего глобального изготовителя косметических средств и парфюмерии L’Oréal.

- 1976: покупка бизнеса по производству консервов Libby, McNeill & Libby.

- 1977: приобретение производителя медикаментозных средств и офтальмологической продукции Alcon Laboratories.

- 1977: концерн получает новый нейм Nestlé S.A.

Тогда же, в 1960-1980-х, начинаются первые скандалы, связанные с детским питанием «Нестле». Концерн в ответ гарантирует «соответствие своей деятельности требованиям Кодекса Всемирной организации здравоохранения (ВОЗ) по маркетингу заменителей грудного молока».

1981-2005: уверенный рост и высокие результаты

Корпорация ставит перед собой амбициозную цель: «Стать лидером в производстве пищевых продуктов и экспертом в области правильного питания и здорового образа жизни». Для этого «Нестле» избавляется от уже неприбыльных брендов и сосредотачивается на активном продвижении продукции для выбранной ЦА — потребителей, заботящихся о своем Здоровье.

- 1981: создание нового бренда здоровых замороженных блюд Stouffer’s Lean Cuisine, отличающихся низкой калорийностью.

- 1981: запуск совместно с «Л’Ореаль» совместного дерматологического предприятия Galderma.

- 1985: вложение $3 млрд в приобретение компании Carnation (США), что позволяет расширить свой ассортимент еще двумя яркими брендами — Carnation и Coffee-Mate.

- 1985: выход на новый для концерна рынок товаров для четвероногих — «Нестле» приобретает Friskies, уже пользующийся мировой популярностью.

- 1986: начало одного из самых успешных брендов — Nespresso. Отныне каждый покупатель мог сделать себе чашечку великолепного кофе не хуже, чем бариста.

- 1988: приобретение кондитерской фабрики Rowntree Mackintosh (Великобритания), пополнение ассортимента новыми сладостями — KitKat, After Eight и Smarties.

- 1988: покупка производителя лакомств, специй и пасты Buitoni-Perugina (Италия).

- 1991: совместно с General Mills компания Nestlé организует совместный проект Cereal Partners Worldwide, чья цель — производить и продвигать готовые быстрые завтраки в глобальном контексте.

- 1991: запуск партнерского (с Coca-Cola Company) предприятия Beverage Partners Worldwide, призванного разрабатывать, производить и продвигать сразу несколько брендов, включая чай «Нести».

- 1992: заключение сделки о покупке производителей минералки France’s Perrier Group, которые в 2002 будут переименованы в Nestlé Waters.

- 1998: приобретение бизнеса по производству минеральной воды San Pellegrino Group (Италия), что ведет за собой запуск в развивающихся государствах новой торговой марки питьевой воды Nestlé Pure Life.

- 2000: презентация в Европе питьевого бренда Aquarel.

- 2000: запуск Sustainable Agricultural Initiative Nestlé — инициативы по сельскому хозяйству «Нестле», направленной на дружественное и взаимовыгодное сотрудничество с местными фермерскими хозяйствами.

- 2001: приобретение американского производителя кормов для животных Ralston Purina для объединения его с Friskies — выходит новый бренд Nestlé Purina Petcare, ставший глобальным лидером в сегменте товаров для питомцев.

- 2002: вложение $2,6 млрд в приобретение производителя замороженных блюд Chef America (США).

- 2002-2003: покупка сразу нескольких изготовителей мороженого — Häagen-Dazs, Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream, Mövenpick.

В данный период развития «Нестле» ощутимо расширяется в Восточной Европе, Америке, Азии и задается целью удержания лидерских позиций по продажам минералки, мороженого и кормов для питомцев.

2006-сейчас: новое время — новый бизнес

Сегодня «Нестле» работает по инновационной стратегии «Создаем общие ценности». В ее рамках принимает участие в программах Nestlé Cocoa Plan и Nescafé Plan, чья цель — разработать и обеспечить должное функционирование экологически безвредных технологий и устойчивых поставок какао-бобов и кофейных зерен.

- 2006: покупка поставщика быстрых завтраков Uncle Toby’s (Австралия).

- 2006: приобретение проекта по разработке и запуску продукции, направленной на контроль массы тела, Jenny Craig.

- 2007: покупка производителя лечебного питания Novartis Medical Nutrition, поставщика минералки Sources Minérales Henniez и фабрики детских смесей Gerber.

- 2010: Kraft Foods продает «Нестле» свое отделение по изготовлению замороженной пиццы.

- 2011: запуск собственных научных подразделений Nestlé Health Science и Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences, призванных разрабатывать на базе последних передовых достижений продукты питания Нового Тысячелетия, способствующие профилактике и терапии хронических болезней.

- 2012: приобретение производителя детского питания Wyeth (Pfizer) Nutrition за $11,9 млрд.

- 2013: приобретение поставщика лечебного питания Pam Lab (США).

- 2014: учреждение нового направления Nestlé Skin Health, для которого у партнера «Л’Ореаль» выкупается доля в совместной дерматологической фабрике Galderma.

- 2015: запуск линейки шоколада «супер-премиум категории» Cailler.

- 2017: расширение на рынке потребительского здравоохранения покупкой Atrium Innovations.

В наши дни Nestlé активно развивает три категории — замороженные продукты, смеси для младенцев, лечебное питание.

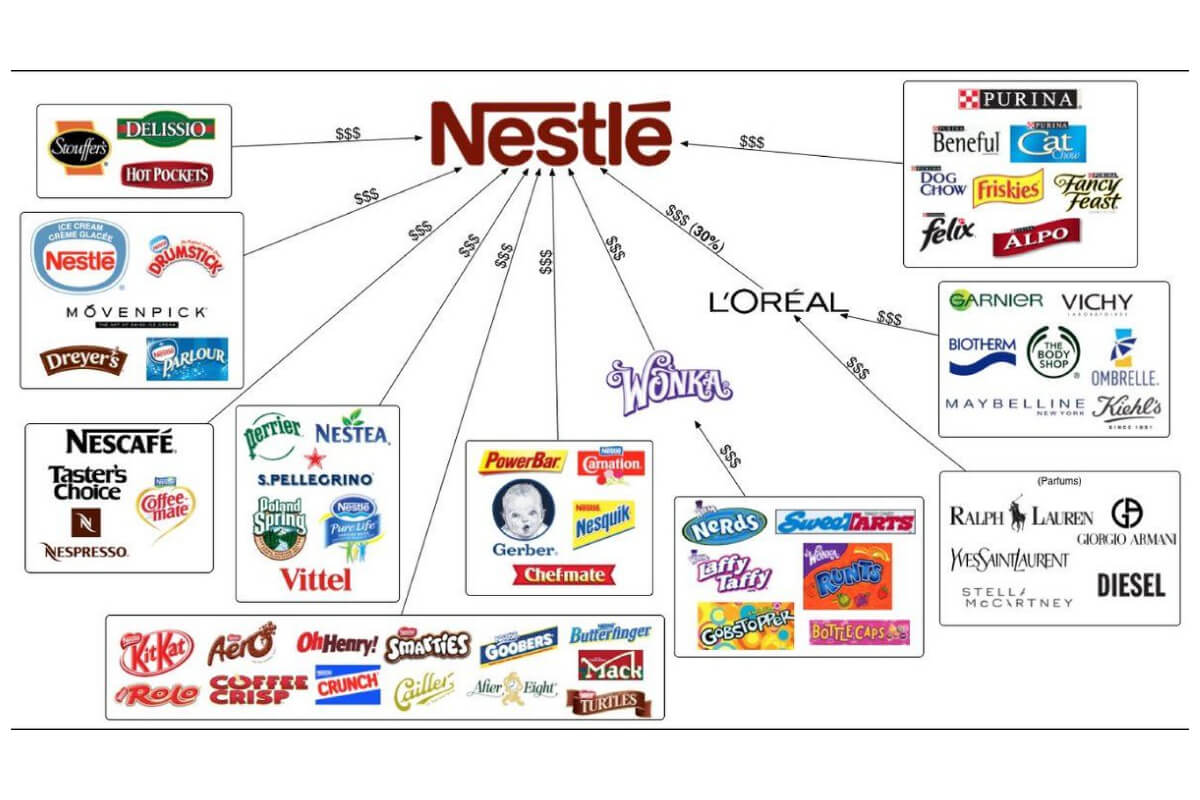

Все бренды «Нестле»: какие продукты производит концерн?

Nestle — крупнейший в мире производитель продуктов питания, который владеет более 2000 брендов! Вспомним самые известные:

- Какао и кофе: Nescafe, Bonka, Nespresso, Caro, Milo, Nesquik.

- Шоколад и кондитерские изделия: Nuts, KitKat, Aero, Cailler, Polo, Toll House, Turtles, Rolo, Merier, Sundy, Galak, Docello, Lanvin, «Россия», «Бон Пари», «Комильфо», «Золотая марка».

- Молочная продукция: Ideal, Carnation, Sveltesse, Dalky, Yoco, Flanby, Chambourcy.

- Полуфабрикаты: Delissio, Herta, Findus, Buitoni, Hot Pockets.

- Детское питание: Nan, Nutrition, Nido, Gerber, Nestogen.

- Готовые завтраки: Cheerios, Fitness, Kosmostars, Nesquik, Chocapic.

- Вода и напитки: Nestea, Contrex, Viladrau, Vittel, Aquarel.

- Мороженое: Maxibon, Movenpick, Extreme, Miko, Fab, Mega.

- Соусы и приправы: Maggi, Thomy, Solis.

- Консервы: Chef, Libby’s, Litoral.

- Клиническое питание: Peptamen, Modulen, Clinutren.

- Корма для животных: Purina, Darling, Friskies, Gourmet, Pro Plan, Alpo, Felix, Dog Show.

Также компания владеет 30 % акций «Л’Ореаль», включающего в себя бренды: Garnier, Vichy, Maybelline, The Body Shop и пр.

Сколько зарабатывает «Нестле», кто владеет компанией?

Представим самые свежие финансовые показатели корпорации:

- Рыночная капитализация (2022): 315,26 млрд CHF.

- Доходность: 87,47 млрд CHF.

- Чистая прибыль: 16,71 млрд CHF.

- Операционные затраты: 27,1 млрд CHF.

- Свободный денежный поток: 9,29 млрд CHF.

- Основные группы товаров: растворимые и жидкие напитки, молочная продукция, детские смеси, медицинское питание, кондитерские изделия, мороженое, полуфабрикаты, корм для животных.

- Основные регионы сбыта: США, Китай, Франция, Бразилия, Великобритания, Мексика, Германия, Филиппины, Канада, Италия, Япония, Россия, Испания, Австралия, Индия.

- Кто владеет компанией (крупнейшие акционеры): Food Products (Holdings) S.A., Nestlé S.A., Norges Bank, BlackRock, Inc., Third Point Management.

Акции компании на момент написания статьи (Июль 2022) торгуются по 114,38 CHF. Всего выпущено 3 млрд ценных бумаг стоимостью в 234 млрд долларов. У частных акционеров — ⅕, остальная доля — у институциональных инвесторов.

5 главных конкурентов Nestlé на современном рынке

Сегодня главными оппонентами «Нестле» являются:

- Unilever — британский производитель продуктов питания и бытовой химиии.

- PepsiCo — транснациональная корпорация, специализирующаяся на пищевой промышленности и безалкогольных напитках.

- Mars — американский изготовитель продуктов питания длительного хранения от шоколадок до кормов для питомцев.

- Kraft Foods — концерн по производству упакованных продуктов питания.

- Groupe Danone — французский производитель молочных и иных продуктов питания.

Однако Nestlé не стоит беспокоиться: ближайший конкурент «Юнилевер» отстает от нее в контексте прибыли в 1,5 раза.

7 секретов успеха от крупнейшего производителя продуктов питания

Как маленький заводик «молочный муки» превратился в многомиллиардный мировой бизнес? Маркетологи выделяют целых семь секретов успеха «Нестле»:

- Системное расширение рынков сбыта, которое не дает упираться в потолок продаж.

- Новаторский подход: «мы не изобретаем, а совершенствуем». Компания не является первооткрывателем абсолютно всех своих продуктов, однако она смогла довести уже существующие разработки до совершенства.

- Использование кризиса как возможности. Первую, Вторую мировые, дефицит бразильского кофе здесь видели как точки роста.

- Создание локальных производств для снижения расходов на логистику.

- Четкое знание своего покупателя, его привычек, традиций, вкусовых предпочтений.

- Промо-акции, близкие клиенту: где-то это красная кружка «Нескафе», напоминающая о Рождестве, а где-то (в Латинской Америке) — плавучий магазин.

- Умение признавать ошибки: компания не игнорирует скандалы, в которых замешана, всегда отвечает на претензии в свой адрес.

Фраза «Великие художники имитируют и улучшают, тогда как плохие — воруют и портят» вполне применима к этой корпорации.

Айдентика: как появился логотип «Нестле»?

Начнем с того, что Анри Нестле был одним первых бизнесменов Швейцарии, создавшим лого для своей компании. Идеей для него стал фамильный герб фармацевта с птицей, сидящей в гнездышке: Nestlé переводится с немецкого как «гнездо». Предприниматель адаптировал иллюстрацию под свой продукт, детское питание, добавив еще троих птенчиков.

Изображение начало использоваться в роли товарного знака с 1868 года. Последний ребрендинг эмблемы случился в 2015: рисунок максимально упростили, чтобы он был читабельным со смартфонов. Кстати, к настоящему времени в логотипе «потерялся» один птенчик — сейчас изображается одна взрослая птица и два детеныша.

«Темная сторона» Nestlé: от обмана с детским питанием до мяса лошадей

Богатая история «Нестле», к сожалению, полна и многочисленными скандалами:

- Многострадальные детские смеси. Пожалуй, самую серьезную и обширную критику за всю историю Nestlé получил за свою линейку детского питания. В частности, компанию обвиняют за «слишком агрессивную» рекламу детских смесей, что побуждает матерей отказываться от грудного вскармливания. Кстати, бойкот детского питания от «Нестле» ведет свою историю с 1977 года — ему даже посвящена отдельная страничка в «Википедии».

- Контроль за ценами на шоколад в Канаде. Антимонопольное бюро провело Расследование, в ходе которого выяснило, что сотрудники «Нестле» встречались с местными производителями лакомства и диктовали им стоимость шоколадок в регионе. Когда факт заговора был доказан, концерн получил штраф на 9 млн долларов.

- Голод в Эфиопии. В 2002, когда ситуация с продовольствием в стране была самой критичной, «Нестле» потребовало, чтобы государство выплатило ей 6 млн долларов долга. От своего решения руководство корпорации отказалось только после того, как получило 8500 писем от несчастных эфиопцев на электронную почту — люди жаловались, что правительство «вытрясает» эти деньги у них.

- Смертельный меламин в детских смесях. В 2008 от питания «Нестле» для грудных младенцев начали умирать Дети: 6 малышей скончались от отказа почечной системы, еще 860 оказались в больнице. Причиной был меламин, найденный в сухих смесях китайского производства. Это слаботоксичный компонент, удешевляющий производство продукта. В 2008 тайваньское Министерство здравоохранения обнаружило меламиновые следы в шести видах продукции бренда.

- «Эко-промывка мозгов». В 2008 концерн запустил пиар-акцию бутилированной воды Nestlé Pure Life: сообщалось, что компания ждет использованные бутылки обратно на повторную переработку. Однако общественность вынудила «Нестле» сказать правду: большая часть собранной тары отправлялась на помойку.

- Мясо лошадей. В консервах «Макароны с говядиной» в 2013 обнаружили лошадиную ДНК, что стало поводом для большого скандала в Италии и Испании.

- Использование детского труда: в 2010 вышел шокирующий д/ф «Темная сторона шоколада», из которого потрясенные зрители узнали, что «Нестле» покупает какао-бобы в Кот-д’иВуаре, где их сбором и выращиванием занимаются дети 12-15 лет. Более того, на плантациях использовался труд маленьких рабов, украденных из соседних государств.

В довершение к сказанному: в 2021 глобальный производитель продуктов питания Nestlé признался, что 60 % его товаров «не подпадает под общепринятые нормы здорового питания». Самыми безопасными назывались вода и молочная продукция, а самыми вредными — пицца Hot Pockets с пепперони и пицца Digorno с мясом на слоеном тесте. Также индекс здорового питания не прошли 99 % мороженого и кондитерского ассортимента.

Интересные факты о Nestlé

Завершим наш рассказ занятной информацией о продуктовой корпорации:

- Настоящее имя основателя — Хайнрих Нестле. Мужчина сменил его на Анри, переехав из Германии в Швейцарию. Чтобы открыть бизнес по производству детского питания, он занял деньги у тети.

- Растворимый кофе «Нескафе» поставляли после Второй Мировой в качестве гуманитарной помощи в Японию.

- На разработку кофемашины и капсульного кофе Nespresso было потрачено более 10 лет.

- Рекорд по прибыли компания поставила в 2010 — показатель достиг 26,3 млрд евро.

В заключение команда бизнес-журнала lindeal.com еще раз отметит, что именно «Нестле» — крупнейший производитель продуктов питания с более чем 150-летней историей. Главными методами его расширения было приобретение брендов, производящих модные для своего времени продукты — мороженое, бульонные кубики, шоколад, сгущенное молоко, замороженные блюда, диетическое и лечебное питание. За время своего существования Nestlé пережила и войны, и кризисы, и бойкоты, и скандалы мирового масштаба, но ничто так и не смогло остановить ее рост, развитие и расширение по всему земному шару.

Швейцарский концерн Nestle – пожалуй, является одним из самых брендов среди производителей продуктов питания. Основан он в 1867 году фармацевтом Г. Нестле. На основе коровьего молока, сахара и пшеничной муки он пытался изготовить продукт, который мог бы заменить грудное молоко. Впоследствии его изобретение помогло существенно снизить смертность среди новорожденных, для которых грудное вскармливание было невозможным.

Спасение. Первым, кто попробовал «Молочную муку Нестле» (такое название получило изобретение фармацевта), стал малыш, родившийся раньше срока. Его организм не воспринимал грудное молоко и существующие на тот момент аналоги, поэтому новый продукт детского питания пришелся как нельзя кстати. Малыш выжил, а «Молочная мука Нестле» приобрела известность и вскоре ее продавали уже по всей Европе.

В 1874 году компанию приобретает Жюль Моннер. Под его началом Nestle будет развиваться, добьется процветания и станет одним из мировых лидеров.

Конкуренция. В это время «Anglo-Swiss Milk Compani», занимающаяся производством сгущенного молока, решил расширить свой ассортимент и начать выпускать свою молочную смесь. В ответ на это, Жюль Моннер занялся производством сгущенки.

Слияние и расширение. Продолжительное время эти две компании были самыми ярыми конкурентами, затем в 1905 году произошло их слияние. Уже к XX веку производство удалось наладить в США, Испании, Англии и Германии. В 1907 году был завоеван австралийский рынок, следующей целью была Азия. Чтобы не возник дефицит, продуктовые склады открыли в Сингапуре, Бомбее и Гонконге.

Трудности. В Первую мировую войну большая часть производства продолжала быть сосредоточенной в Европе. Когда начались полномасштабные боевые действия компания начала испытывать серьезные трудности: сырье приходило с большой задержкой или не поступало вовсе, а сбывать готовую продукцию становилось все сложнее.

Спасти от краха Nestle помогли правительственные заказы на сухую сгущенку. Именно на этот продукт в те годы был огромный спрос.

Но, как оказалось, главное испытание было впереди. С окончанием войны ситуация на рынке резко ухудшилась. Сырье сильно подорожало, правительственные заказы больше не поступали, а покупатели предпочли сухому молоку свежее. Все это привело к тому, что 1921 год компания проработала в убыток.

Выйти из непростой ситуации помог Л. Даплес – банковский эксперт. Он провел реорганизацию и помог наладить работу компании. Nestle же расширила свой ассортимент за счет шоколада, а в 1938 году на прилавках появился Nescafe – растворимый кофе, быстро завоевавший сердца потребителей.

Испытание. В 1939 году грядет еще одно испытание – начало Второй мировой войны. Швейцария поддерживала нейтралитет, а позже перешла на изоляцию. Благодаря выпускаемому кофе Nestle не только удалось удержаться на плаву, но и получить хорошую прибыль. Американские военные оценили напиток по достоинству и стали основными его потребителями, уже к концу войны концерн считался мировым лидером по продаже кофе.

Рост ассортимента. Вскоре Nestle начинает выкупать компании, занимающиеся производством пищевых продуктов, что позволяет существенно расширить ассортимент концерна:

— приобретение Maggi;

— в 1950 году был куплен английский производитель консервированных продуктов;

— в 1963 и 1973 году выкупаются производители замороженных продуктов;

— в 1971 – ассортимент пополняют фруктовые соки.

В 1974 году Nestle становится главным акционером косметической фирмы L’Oreal. И в этом же году концерн снова начинает испытывать трудности. Кризис происходит из-за падения мировых цен на нефть, замедления экономического роста и др. Но и в этот раз удается избежать существенных потерь.

Nestle сегодня. В 90-е годы концерн открывает для себя рынки Восточной Европы и Китая. В новое тысячелетие он входит мировым лидером по производству продуктов питания. Сегодня Nestle – бренд, известный во всех уголках Земного шара. Компания продолжает развиваться и удерживать лидирующие позиции.

Nestle — крупнейшая в мире компания, которая производит продукты питания, корма для животных, косметику. Девиз компании — «Качество продуктов, качество жизни». Nestle предлагает потребителям вести здоровый образ жизни, приобретая лишь качественные и проверенные продукты. С чего же начиналась история известнейшего на сей день бренда?

Содержание

- 1 Начало пути

- 2 Что принесли с собой Мировые Войны?

- 3 Новые слияния

- 4 Начинающиеся изменения

- 5 Работа в 90-е года прошлого века

- 6 Компания Nestle сегодня

- 7 Nestle в России

Начало пути

Фармацевт из Швейцарии по имени Анри Нестле в конце XIX века был озадачен созданием смеси для детского питания, которая в точности бы повторяла молоко матери. На исследования его двигает жена Клементина, дочь врача. Она часто помогала отцу и видела немало детских смертей. Клементина знала, что проблемы с питанием — одна из частых причин гибели младенцев. Она просит мужа помочь. И ему это удается! Анри выпускает « Farine Lactee Henry Nestle», состоящий из молока, муки и сахара.

Воодушевленный успехом, фармацевт решает открыть собственную небольшую компанию, которая занималась бы производством молока. Ему удается это сделать уже в 1867 году. Анри Нестле переносит фамильный герб (гнездо с тремя птенчиками) на логотип компании.

Один торговый агент предлагал фармацевту сменить знак на крест, находящийся на флаге Швейцарии, но тот твердо отказал. В 1988 году герб претерпевает изменение — вместо трех птенцов на нем оказывается два. Это простая ассоциация с семьями того времени. Европейцы и американцы конца XX века чаще всего имели двоих детей.

Первый клиент. Первым клиентом компании стал малыш, страдающей аллергией на грудное молоко. Не переносил бедный младенец и коровье молоко. Врачи разводили руками. Анри Нестле предложил ребенку сухую смесь собственного производства, и она не вызвала аллергии! Ребенок был спасен благодаря компании Nestle. Случай вызвал ажиотаж в стране и смеси фармацевта начали быстро раскупать не только в Швейцарии, но и на территории всей Европы. Карман Анри постепенно полнел.

Конкуренты Чарльз и Джордж Пейжди тоже не сидели сложа руки. Их завод по производству сгущенного молока с 70-х годов XIX века начинает выпускать смесь для детского питания. Завод Nestle не стерпел и наладил выпуск сгущённого молока в ответ. До 1905 года две компании были жесткими конкурентами на молочном рынке. В это время Нестле уже открыли заводы в Испании, Германии, США и Великобритании. В 1905 году две компании сливаются, и образуется Nestle and Anglo-Swiss Milk Company. С этого времени владельцы начинают активную работу по расширению рынка продаж, начиная захватывать Австралию.

Полезное видео: корпоративный фильм о истории.

Что принесли с собой Мировые Войны?

Первая мировая война принесла с собой серьезные проблемы. Вся мощь производства компании находилась на территории «Старого Света», но путь туда был практически закрыт. Почти все запасы свежего молока подошли к концу. Зато населению требовалось большое количество сухого и сгущенного молока — это и спасло компанию в трудные времена. Благодаря правительственному заказу для армии Nestle уверенно держится на плаву в оставшееся военное время. Компания даже выкупает несколько заводов в США. Когда война заканчивается, Nestle имеет почти 40 заводов — это вдвое больше по сравнению с 1914 годом.

Интересный факт. Многие ассоциируют компанию именно с шоколадом, а ведь он составляет всего три процента от общего объема продаж.

Послевоенное время достаточно сильно ударяет по производству. Сырье дорожает, курс валют падает… Экономика затихла. В это трудное время и появляется Луис Даплес — банковский эксперт, спасший компанию от краха. Реформировав производство, он налаживает торговлю вновь. В это же время Nestle расширяет товарный ряд. В продажу поступает шоколад, молоко с солодом, детская порошковая паста и всем известный кофе Nescafe, произведший настоящий фурор!

Во время Второй мировой войны Nestle снова расширяет объёмы продаж. Кофе, сгущенка и шоколад буквально улетают с прилавков. Если в 1943 году доход был равен 100 млн долларов, то к 1945 – 245 млн и именно Nescafe приносит компании этот успех.

Новые слияния

В послевоенные годы Nestle активно пополняет свое производство и расширяет ассортимент. Слияние с компаниями Alimentana S.A и Maggi дает возможность продавать супы быстрого приготовления и приправы. В 1950 году к Нестле присоединяется Crosse & Blackwell, а в 1963 году — Findus. Теперь компания продает консервированные супы и замороженные продукты. В 1971 году после слияния с маркой Libby, Нестле налаживает производство и продажу фруктовых соков. К 1974 году объемы продаж компании взлетают на 50%.

Начинающиеся изменения

В 1974 году компания Нестле выходит за рамки пищевой торговли и приобретает акции известной косметической марки L’Oreal. Делается это для сохранения равновесия. Ведь цены на какао-бобы растут вдвое, а на кофе — втрое. Для этой же цели компания скупает акции фармацевтической фирмы Alcon Laboratories Inc. Нестле остается на плаву и начиная с 90-х годов XX века, ликвидирует барьеры торговли. Открываются новые европейские и китайские рынки сбыта…

Работа в 90-е года прошлого века

В 1997 году советом директоров было принято решение о покупке итальянской марки питьевой воды San Pellegrino. В этом же году компанию возглавляет Питер Брабек-Летман, который предпочитал вкладывать деньги в наиболее прибыльные направления рынка. Чуть позже скуплена марка Spiller Petfoods. Но самым крупным делом компании стало слияние с фирмой Carnation. Ее марка Friskies, которую Нестле приобрела за 3 млрд долларов, приносит компании небывалый доход и прочно ставит на рынок торговли кормами для домашних любимцев. Брабек считается одним из самых деятельных директоров компании, который почти полностью перестроил ее.

Компания Nestle сегодня

Сегодня трудно встретить человека, который бы не слышал о компании Nestle и не пробовал ее продукцию. В любом магазине можно найти детское питание, кофе, быстрые завтраки и другие продукты от Nestle. Компания владеет огромным количеством заводов по всему миру, в том числе и в России. Более 60 стран мира любят и уважают эту марку!

Это интересно. Нестле принадлежит 461 фабрика по всему миру, 83 страны и 330 тысяч рабочих заняты производством товаров.

Nestle в России

Нестле начинают свои деловые отношения с Россией в далеком XIX веке. Александр Венцель подписывает контракт на поставку молочной продукции в наши земли, тем самым открывая сотрудничество с маркой на долгие годы.

Новый виток отношений приходится лишь на XX век. В 90-х годах активно развивается дистрибьюторская сеть, предлагающая населению в основном кофе. Уже в 1996 году Нестле становится полноценной компанией России, наладив систему сбыта и импорта. В 2007 году компания получает новое имя на территории нашей страны «Нестле-Россия».

Конкуренты. Основные конкуренты компании — PepsiCo, Mars, Unilever.

Сегодня Nestle – это крупнейшая компания по продаже продуктов питания и напитков. Многолетний успех — это не простое стечение обстоятельств. Это результат упорной работы, трудолюбия совета директоров, который не опускал руки в самые сложные времена. Активное продвижение торговых марок, постоянные слияния с более мелкими компаниями, бесконечное расширение рынка сбыта — все это привело компанию Nestle к ошеломительному успеху!

Полезное видео: корпоративный фильм о деятельности в России.

|

|

Headquarters in Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland |

|

| Formerly |

List

|

|---|---|

| Type | Public (SA) |

|

Traded as |

SIX: NESN |

| ISIN | CH0038863350 |

| Industry | Food processing |

| Founded | 1866; 157 years ago (for the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company branch) |

| Founder | Henri Nestlé (for the Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé branch) |

| Headquarters | Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland |

|

Area served |

Worldwide |

|

Key people |

|

| Products | Baby food, coffee, dairy products, breakfast cereals, confectionery, bottled water, ice cream, pet foods (list…) |

| Revenue | |

|

Operating income |

|

|

Net income |

|

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

|

Number of employees |

275,000 (2022)[3] |

| Subsidiaries | Cereal Partners Worldwide (50%) |

| Website | nestle.com |

| Footnotes / references [3][4] |

Nestlé S.A.[a] ( NESS-lay, -lee, -əl,[5] French: [nɛsle], German: [ˈnɛstlə] (listen)) is a Swiss multinational food and drink processing conglomerate corporation headquartered in Vevey, Vaud, Switzerland. It has been the largest publicly held food company in the world, measured by revenue and other metrics, since 2014.[6][7][8][9][10] It ranked No. 64 on the Fortune Global 500 in 2017[11] and No. 33 in the 2016 edition of the Forbes Global 2000 list of the largest public companies.[12]

Nestlé’s products include baby food (some including human milk oligosaccharides), medical food, bottled water, breakfast cereals, coffee and tea, confectionery, dairy products, ice cream, frozen food, pet foods, and snacks. Twenty-nine of Nestlé’s brands have annual sales of over 1 billion CHF (about US$1.1 billion),[13] including Nespresso, Nescafé, Kit Kat, Smarties, Nesquik, Stouffer’s, Vittel, and Maggi. Nestlé has 447 factories, operates in 189 countries, and employs around 339,000 people.[14] It is one of the main shareholders of L’Oreal, the world’s largest cosmetics company.[15]

Nestlé was formed in 1905 by the merger of the «Anglo-Swiss Milk Company», which was established in 1866 by brothers George and Charles Page, and «Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé» founded in 1867 by Henri Nestlé.[16] The company grew significantly during the World War I and again following World War II, expanding its offerings beyond its early condensed milk and infant formula products. The company has made a number of corporate acquisitions including Crosse & Blackwell in 1950, Findus in 1963, Libby’s in 1971, Rowntree Mackintosh in 1988, Klim in 1998, and Gerber in 2007.

The company has been associated with various controversies, facing criticism and boycotts over its marketing of baby formula as an alternative to breastfeeding in developing countries (where clean water may be scarce), its reliance on child labour in cocoa production, and its production and promotion of bottled water.

History

1866–1900: Founding and early years

Henri Nestlé (1814–1890), a German-born Swiss confectioner, was the founder of Nestlé and one of the main creators of condensed milk.

Nestlé’s origin dates back to the 1860s when two separate Swiss enterprises were founded that would later form Nestlé. In the following decades, the two competing enterprises expanded their businesses throughout Europe and the United States.[17]

Timeline

- 1866: Charles Page (US consul to Switzerland) and George Page, brothers from Lee County, Illinois established the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company in Cham, Switzerland. The company’s first British operation was opened at Chippenham, Wiltshire in 1873.[18][19]

- 1867: In Vevey, Switzerland, Henri Nestlé developed milk-based baby food and soon began marketing it. The following year, Daniel Peter began seven years of work perfecting the milk chocolate manufacturing process. Nestlé had the solution Peter needed to fix his problem of removing all the water from the milk added to his chocolate, thus preventing the product from developing mildew.

- 1875: Henri Nestlé retired; the company, under new ownership, retained his name as Société Farine Lactée Henri Nestlé.[citation needed]

- 1877: Anglo-Swiss added milk-based baby foods to its products; in the following year, the Nestlé Company added condensed milk to its portfolio, which made the firms direct rivals.

- 1879: Nestlé merged with milk chocolate inventor Daniel Peter.[20]

- 1890: Henri Nestlé dies.

1901–1989: Mergers

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Henri Nestlé and his successors participated in the development of the chocolate industry in Switzerland, together with the Peter, Kohler, and Cailler families.[21] In 1904, Daniel Peter and Charles-Amédée Kohler (son of Charles-Amédée Kohler who founded a chocolate factory in 1830) became partners and founded the Société générale suisse des chocolats Peter et Kohler réunis. in 1911, the company created by Peter and Kohler merged with Cailler.[22] Alexandre Cailler (grandson of François-Louis Cailler) had founded a chocolate factory in Broc in 1898, still used by Nestlé today; which enabled the production of milk chocolate on a large scale. In 1929, Peter, Cailler, Kohler, Chocolats Suisses finally merged with the Nestlé group.[23][24] An earlier alliance in 1904 between Peter and Nestlé also allowed the production of milk chocolate in the United States, at the Fulton plant.[25]

In 1905, Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss merged to become the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Company, retaining that name until 1947 when the name ‘Nestlé Alimentana SA’ was taken as a result of the acquisition of Fabrique de Produits Maggi SA (founded 1884) and its holding company, Alimentana SA, of Kempttal, Switzerland. The company’s current name was adopted in 1977. By the early 1900s, the company was operating factories in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and Spain.[26] The First World War created a demand for dairy products in the form of government contracts, and by the end of the war, Nestlé’s production had more than doubled.

Certificate for 100 shares of the Nestlé and Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Co., issued 1. November 1918

In January 1919, Nestlé bought two condensed milk plants in Oregon from the company Geibisch and Joplin for $250,000. One was in Bandon, while the other was in Milwaukie. They expanded them considerably, processing 250,000 pounds of condensed milk daily in the Bandon plant.[27]

Aleppo Nestlé building Tilal street 1920s

After the World War I, government contracts dried up, and consumers switched back to fresh milk. However, Nestlé’s management responded quickly, streamlining operations and reducing debt. The 1920s saw Nestlé’s first expansion into new products, with chocolate-manufacture becoming the company’s second most important activity; white chocolate was created in the following decade. Louis Dapples was CEO till 1937 when succeeded by Édouard Muller till his death in 1948.

Nestlé felt the effects of the Second World War immediately. Profits dropped from US$20 million in 1938 to US$6 million in 1939.[28] Factories were established in developing countries, particularly in South America.[29] Ironically, the war helped with the introduction of the company’s newest product, Nescafé («Nestlé’s Coffee»), which became a staple drink of the US military. Despite that, Nestlé actually supplied both sides in the war: the company had a contract to feed the German army. Nestlé’s production and sales rose in the wartime economy.[29]

The logo that Nestlé used from 1938 to 1966[30]

The end of World War II was the beginning of a dynamic phase for Nestlé. Growth accelerated and numerous companies were acquired. In 1947 Nestlé merged with Maggi, a manufacturer of seasonings and soups. Crosse & Blackwell followed in 1950, as did Findus (1963), Libby’s (1971), and Stouffer’s (1973).[31] Diversification came under chairman & CEO Pierre Liotard-Vogt with a shareholding in L’Oreal in 1974 and the acquisition of Alcon Laboratories Inc. in 1977 for $280 million.[31]

In the 1980s, Nestlé’s improved bottom line allowed the company to launch further acquisitions. Carnation was acquired for US$3 billion in 1984 and brought the evaporated milk brand, as well as Coffee-Mate and Friskies to Nestlé. In 1986, the company founded Nestlé Nespresso S.A. The British confectionery company Rowntree Mackintosh was acquired in 1988 for $4.5 billion, which brought brands such as Kit Kat, Rolo, Smarties, and Aero.[32]

1990–2011: Growth internationally

The first half of the 1990s proved to be favourable for Nestlé. Trade barriers crumbled, and world markets developed into more or less integrated trading areas. Since 1996, there have been various acquisitions, including San Pellegrino (1997), D’Onofrio (1997), Spillers Petfoods (1998), and Ralston Purina (2002). There were two major acquisitions in North America, both in 2002 – in June, Nestlé merged its US ice cream business into Dreyer’s, and in August, a US$2.6 billion acquisition was announced of Chef America, the creator of Hot Pockets. In the same time-frame, Nestlé entered in a joint bid with Cadbury and came close to purchasing the American company Hershey’s, one of its fiercest confectionery competitors, but the deal eventually fell through.[33]

In December 2005, Nestlé bought the Greek company Delta Ice Cream for €240 million.[34] In January 2006, it took full ownership of Dreyer’s, thus becoming the world’s largest ice cream maker, with a 17.5% market share.[35] In June 2006, Nestlé purchased weight-loss company Jenny Craig for US$600 million.[36] In July 2007, completing a deal announced the year before, Nestlé acquired the Medical Nutrition division of Novartis Pharmaceutical for US$2.5 billionand also acquiring the milk-flavoring product known as Ovaltine, the «Boost» and «Resource» lines of nutritional supplements, and Optifast dieting products.[37]

In April 2007, returning to its roots, Nestlé bought US baby-food manufacturer Gerber for US$5.5 billion.[38][39][40] In December 2007, Nestlé entered into a strategic partnership with a Belgian chocolate maker, Pierre Marcolini.[41]

Nestlé agreed to sell its controlling stake in Alcon to Novartis on 4 January 2010. The sale was to form part of a broader US$39.3 billion offer by Novartis for full acquisition of the world’s largest eye-care company.[42] On 1 March 2010, Nestlé concluded the purchase of Kraft Foods’s North American frozen pizza business for US$3.7 billion.

Since 2010, Nestlé has been working to transform itself into a nutrition, health and wellness company in an effort to combat declining confectionery sales and the threat of expanding government regulation of such foods. This effort is being led through the Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences under the direction of Ed Baetge. The institute aims to develop «a new industry between food and pharmaceuticals» by creating foodstuffs with preventive and corrective health properties that would replace pharmaceutical drugs from pill bottles. The Health Science branch has already produced several products, such as drinks and protein shakes meant to combat malnutrition, diabetes, digestive health, obesity, and other diseases.[43]

In July 2011, Nestlé SA agreed to buy 60 percent of Hsu Fu Chi International Ltd. for about US$1.7 billion.[44] On 23 April 2012, Nestlé agreed to acquire Pfizer Inc.’s infant-nutrition, formerly Wyeth Nutrition, unit for US$11.9 billion, topping a joint bid from Danone and Mead Johnson.[45][46][47]

2012–present

In recent years, Nestlé Health Science has made several acquisitions. It acquired Vitaflo, which makes clinical nutritional products for people with genetic disorders; CM&D Pharma Ltd., a company that specialises in the development of products for patients with chronic conditions like kidney disease; and Prometheus Laboratories, a firm specialising in treatments for gastrointestinal diseases and cancer. It also holds a minority stake in Vital Foods, a New Zealand-based company that develops kiwifruit-based food products as of 2012.[48]

Nestlé sold its Jenny Craig business unit to North Castle Partners in 2013.[49] In February 2013, Nestlé Health Science bought Pamlab, which makes medical foods based on L-methylfolate targeting depression, diabetes, and memory loss.[50] In February 2014, Nestlé sold its PowerBar sports nutrition business to Post Holdings, Inc.[51] Later, in November 2014, Nestlé announced that it was exploring strategic options for its frozen food subsidiary, Davigel.[52]

In December 2014, Nestlé announced that it was opening 10 skin care research centres worldwide, deepening its investment in a faster-growing market for healthcare products. That year, Nestlé spent about $350 million on dermatology research and development. The first of the research hubs, Nestlé Skin Health Investigation, Education and Longevity Development (SHIELD) centres, will open mid 2015 in New York, followed by Hong Kong and São Paulo, and later others in North America, Asia, and Europe. The initiative is being launched in partnership with the Global Coalition on Aging (GCOA), a consortium that includes companies such as Intel and Bank of America.[53]

In January 2017, Nestlé announced that it was relocating its US headquarters from Glendale, California, to Rosslyn, Virginia, outside of Washington, DC.[54]

In March 2017, Nestlé announced that they will lower the sugar content in Kit Kat, Yorkie and Aero chocolate bars by 10% by 2018.[55] In July, a similar announcement followed concerning the reduction of sugar content in its breakfast cereals in the UK.[56]

The company announced a $20.8 billion share buyback in June 2017, following the publication of a letter written by Third Point Management founder Daniel S. Loeb, Nestlé’s fourth-largest stakeholder with a $3.5 billion stake,[57] explaining how the firm should change its business structure.[58] Consequently, the firm will reportedly focus investment on sectors such as coffee and pet care and will seek acquisitions in the consumer health-care industry.[58]

In 2016, Nestlé and PAI Partners establish a joint venture, Froneri, to combine the two companies’ ice cream activities throughout Europe and other international countries.[59]

In July 2017, Nestlé introduced a new type of infant formula in Spain, containing two human milk oligosaccharides.[60] Oligosaccharides are the third most abundant components of breast milk with various health benefits, but previously were not part of infant formula.

In September 2017, Nestlé S.A. acquired a majority stake of Blue Bottle Coffee.[61] While the deal’s financial details were not disclosed, the Financial Times reported «Nestlé is understood to be paying up to $500m for the 68 per cent stake in Blue Bottle».[62]

In September 2017, Nestlé USA agreed to acquire Sweet Earth, a California-based producer of plant-based foods, for an undisclosed sum.[63]

In January 2018, Nestlé USA announced it was selling its US confectionary business to Ferrara Candy Company, an Italian chocolate and candy maker.[64] The company was sold for a total of an estimated $2.8 billion.[64]

In May 2018, it was announced that Nestlé and Starbucks struck a $7.15 billion distribution deal, which allows Nestlé to market, sell and distribute Starbucks coffee globally and to incorporate the brand’s coffee varieties into Nestlé’s proprietary single-serve system, expanding the overseas markets for both companies.[65]

Nestlé set a new profit target in September 2017 and agreed to offload over 20 of its US candy brands in January 2018. However, sales grew only 2.4% in 2017, and as of July 2018, the share price declined more than 8%. While some suggestions were adopted, Loeb said in a July 2018 letter that the shifts are too small and too slow. In a statement, Nestlé wrote that it was «delivering results» and listed actions it had taken, including investing in key brands and its global coffee partnership with Starbucks. However, activist investors disagreed, leading Third Point Management to launch NestleNOW, a website to push its case with recommendations calling for change, accusing Nestlé of not being as fast, aggressive, or strategic as it needs to be. Activist investors called for Nestlé to divide into three units with distinct CEOs, regional structures, and marketing heads — beverage, nutrition, and grocery; spin off more businesses that do not fit its model such as ice cream, frozen foods, and confectionery; and add an outsider with expertise in the food and beverage industry to the board.[66][67]

In September 2018, Nestlé announced that it would sell Gerber Life Insurance for $1.55 billion.[68][69]

In October 2018, Nestlé announced the launch of the Nestlé Alumni Network, through a strategic partnership with SAP & EnterpriseAlumni, to engage with their over 1 million alumni globally.[70]

In 2019, the company announced that it would publish Nutri-Score on all of its products sold in the European countries that supported the nutritional label.[71]

In 2020, Nestlé USA’s and Nestlé Canada’s ice cream divisions were acquired by Froneri.[72] Also during that year, Nestlé announced that the company wants to invest in plant-based food, starting with a «tuna salad» and meat-free products to engage and reach younger and vegan consumers.[73]

On 16 February 2021, Nestlé announced that it had agreed to sell its water brands in the US and Canada to One Rock Capital Partners and Metropoulos & Co. The sale would include the spring water and mountain brands, the purified water brand and the delivery service. The plan did not include the Perrier, S.Pellegrino and Acqua Panna brands.[74][75] In early April 2021, the sale was concluded.[76]

The COVID-19 pandemic did not affect Nestlé negatively. Due to lockdowns, people bought more packaged foods, not only coffee and dairy products, but also pet products, which increased the company’s sales. Nestlé is recording its strongest quarterly sales growth in 10 years.[77]

In April 2021, Nestlé agreed to purchase the vitamin manufacturing Bountiful Company, formerly known as The Nature’s Bounty Co., for $5.75 billion, noting as well that much of the company’s growth that quarter came from «vitamins, minerals, and supplements that support health and the immune system». The deal acquires various assets from Bountiful, including Nature’s Bounty, Solgar, Osteo Bi-Flex, and Puritan’s Pride.[78][79][80]

In January 2022, Nestlé will pay cocoa farmers cash if they send their children to school.[81]

In May 2022, it was announced Nestlé’s Health Science unit had acquired the Brazilian organic, natural, plant-based food maker Puravida.[82]

In May 2022, Nestle was sending baby formula supplies to the U.S. from European air bases to ease the 2022 United States infant formula shortage. These relief shipments included products from the Gerber baby food formula brand from the Netherlands and Alfamino baby formula from Switzerland.[83]

Corporate affairs and governance

Nestlé Japan headquarters in Nestlé House building, Kobe, Japan

Capital ownership of Nestlé by country of origin as of 2014:[84]

Switzerland (35.28%)

United States (28.53%)

All others (36.19%)

Nestlé is the biggest food company in the world, with a market capitalisation of roughly 231 billion Swiss francs, which is more than US$247 billion as of May 2015.[85] Nestlé has a primary listing on the SIX Swiss Exchange and is a constituent of the Swiss Market Index. It previously had a secondary listing on Euronext.

In 2014, consolidated sales were CHF 91.61 billion and net profit was CHF 14.46 billion. Research and development investment was CHF 1.63 billion.[86]

- Sales per category in CHF[87][14]

- 20.3 billion powdered and liquid beverages

- 16.7 billion milk products and ice cream

- 13.5 billion prepared dishes and cooking aids

- 13.1 billion nutrition and health science

- 11.3 billion pet care

- 9.6 billion confectionery

- 6.9 billion water

- Percentage of sales by geographic area breakdown[87][14]

- 43% from Americas

- 28% from Europe

- 29% from Asia, Oceania and Africa

According to a 2015 global survey of online consumers by the Reputation Institute, Nestlé has a reputation score of 74.5 on a scale of 1 to 100.[88]

Financial data

| Year | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 83.642 | 92.186 | 92.158 | 91.612 | 88.785 | 89.469 | 89.791 | 91.439 | 92.568 | 84.343 | 87.088 |

| Net income | 9.487 | 10.611 | 10.015 | 14.456 | 9.066 | 8.531 | 7.183 | 10.135 | 12.609 | 12.232 | 17.196 |

| Assets | 114.091 | 126.229 | 120.442 | 133.450 | 123.992 | 131.901 | 130.380 | 137.015 | 127.940 | 124.028 | 139.142 |

| Employees | 328,000 | 339,000 | 333,000 | 339,000 | 335,000 | 328,000 | 323,000 | 308,000 | 291,000 | 273,000 | 276,000 |

Joint ventures

Joint ventures include:

- Cereal Partners Worldwide with General Mills (50%/50%)[90]

- Beverage Partners Worldwide with The Coca-Cola Company (50%/50%), closed in 2018.[91]

- Froneri with PAI Partners (50%/50%)

- Lactalis Nestlé Produits Frais with Lactalis (40%/60%)[92]

- Nestlé Colgate-Palmolive with Colgate-Palmolive (50%/50%)[93]

- Nestlé Indofood Citarasa Indonesia with Indofood (50%/50%)[94]

- Nestlé Snow with Snow Brand Milk Products (50%/50%)[95]

- Nestlé Modelo with Grupo Modelo

- Dairy Partners America Brasil with Fonterra (51%/49%)

Board of directors

As of 2017, the board is composed of:[96]

- Paul Bulcke, chairman and former CEO of Nestlé

- Andreas Koopmann, former CEO of Bobst

- Beat Hess, former legal director/general counsel for ABB Group and Royal Dutch Shell

- Renato Fassbind, former CEO of DKSH and former CFO of Credit Suisse

- Steven George Hoch, founder of Highmount Capital

- Naina Lal Kidwai, former CEO of HSBC Bank India, country head for HSBC in India

- Jean-Pierre Roth, former chairman of the Swiss National Bank

- Ann Veneman, former United States Secretary of Agriculture and director of UNICEF

- Henri de Castries, former CEO and chairman of AXA

- Eva Cheng, former executive vice president of China and Southeast Asia for Amway

- Ruth Khasaya Oniang’o, former member of the Parliament of Kenya, current professor at Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy

- Patrick Aebischer, former president of École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

Lobbying

The company engages third party lobbying firms to engage with parliaments and governments in various jurisdictions. For example, in South Australia the company engages Etched Communications.[97] In the US, Nestlé has a strong influence in Washington, D.C. From 2015 to 2020 their average spend on lobbying was $1,951,667 each year.[98]

Products

Samples of Nestlé Toll House Cafe items in 2012

Nestlé currently has over 2,000 brands[99][100] with a wide range of products across a number of markets, including coffee, bottled water, milkshakes and other beverages, breakfast cereals, infant foods, performance and healthcare nutrition, seasonings, soups and sauces, frozen and refrigerated foods, and pet food.[14] In 2019, the company entered the plant-based food production business with its Incredible and Awesome Burgers (under the Garden Gourmet and Sweet Earth brands). In 2020, Nestlé announced additional plant-based products including soy-based bratwurst and chorizo-like sausages.[101]

Music and entertainment

In 1993, plans were made to update and modernise the overall tone of Walt Disney’s EPCOT Center, including a major refurbishment of The Land pavilion. Kraft Foods withdrew its sponsorship on 26 September 1993, with Nestlé taking its place. Co-financed by Nestlé and the Walt Disney World Resort, a gradual refurbishment of the pavilion began on 27 September 1993.[102] In 2003, Nestlé renewed its sponsorship of The Land; however, it was under agreement that Nestlé would oversee its own refurbishment to both the interior and exterior of the pavilion. Between 2004 and 2005, the pavilion underwent its second major refurbishment. Nestlé stopped sponsoring The Land in 2009.[103]

On 5 August 2010, Nestlé and the Beijing Music Festival signed an agreement to extend by three years Nestlé’s sponsorship of this international music festival. Nestlé has been an extended sponsor of the Beijing Music Festival for 11 years since 2000. The new agreement will continue the partnership through 2013.[104]

Nestlé has partnered the Salzburg Festival in Austria for 20 years. In 2011, Nestlé renewed its sponsorship of the Salzburg Festival until 2015.[105]

Together, they have created the «Nestlé and Salzburg Festival Young Conductors Award», an initiative that aims to discover young conductors globally and to contribute to the development of their careers.[106]

Sports

Nestlé’s sponsorship of the Tour de France began in 2001 and the agreement was extended in 2004, a move which demonstrated the company’s interest in the Tour. In July 2009, Nestlé Waters and the organisers of the Tour de France announced that their partnership will continue until 2013. The main promotional benefits of this partnership will spread on four key brands from Nestlé’s product portfolio: Vittel, Powerbar, Nesquik, or Ricore.[107]

On 27 January 2012, the International Association of Athletics Federations announced that Nestlé will be the main sponsor for the further development of IAAF’s Kids’ Athletics Programme, which is one of the biggest grassroots development programmes in the world of sports. The five-year sponsorship started in January 2012.[108] On 11 February 2016, Nestlé decided to withdraw its sponsorship of the IAAF’s Kids’ Athletics Programmes because of doping and corruption allegations against the IAAF. Nestlé followed suit after other large sponsors, including Adidas, also stopped supporting the IAAF.[109]

In 2014, Nestlé Waters sponsored the UK leg of the Tour de France through its Buxton Natural Mineral Water brand.[110]

In 2002, Nestlé announced it was main sponsor for the Great Britain Lionesses Women’s rugby league team for the team’s second tour of Australia with its Munchies product.[111]

Nestlé supports the Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) on a number of nutrition and fitness fronts, funding a Fellowship position in AIS Sports Nutrition; nutrition activities in the AIS Dining Hall; research activities; and the development of education resources for use at the AIS and in the public domain.[112]

Controversies and criticisms

Baby formula marketing

Concern about Nestlé’s «aggressive marketing» of their breast milk substitutes, particularly in less economically developed countries (LEDCs), first arose in the 1970s.[113] Critics have accused Nestlé of discouraging mothers from breastfeeding and suggesting that their baby formula is healthier than breastfeeding, despite there being no evidence for this.[citation needed] This led to a boycott which was launched in 1977 in the United States and subsequently spread into Europe.[114][115] The boycott was officially suspended in the US in 1984, after Nestlé agreed to follow an international marketing code endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO),[114][116][117] but was relaunched in 1989.[118] As of 2011, the company is included in the FTSE4Good Index designed to help enable ethical investment.[119][120][121][122]

However, the company allegedly repeated these same marketing practices in developing countries like Pakistan in the 1990s. A Pakistani salesman named Syed Aamir Raza Hussain became a whistle-blower against his former employer Nestlé. In 1999, two years after he left Nestlé, Hussain released a report in association with the non-profit organisation, Baby Milk Action, in which he alleged that Nestlé was encouraging doctors to push its infant formula products over breastfeeding. Nestlé has denied Raza’s allegations.[123] This story inspired the acclaimed 2014 Indian film Tigers by the Oscar-winning Bosnian director Danis Tanović.

In May 2011, nineteen Laos-based international NGOs, including Save the Children, Oxfam, CARE International, Plan International, and World Vision launched a boycott of Nestlé with an open letter.[124] Among other unethical practices, they criticised a failure to translate labelling and health information into local languages and accused the company of giving incentives to doctors and nurses to promote the use of infant formula.[125] Nestlé denied the claims and responded by commissioning an audit, carried out by Bureau Veritas, which concluded that «the requirements of the WHO Code and Lao PDR Decree are well embedded throughout the business» but that they were violated by promotional materials «in 4% of the retail outlets visited».[126]

Ernest W. Lefever and the Ethics and Public Policy Center were criticized for accepting a $25,000 contribution from Nestlé while the organization was in the process of developing a report investigating medical care in developing nations which was never published. It was alleged that this contribution affected the release of the report and led to the author of the report submitting an article to Fortune magazine praising the company’s position.[127]

Nestlé has been under investigation in China since 2011 over allegations that the company bribed hospital staff to obtain the medical records of patients and push its infant formula to increase sales.[128] This was found to be in violation of a 1995 Chinese regulation that aims to secure the impartiality of medical staff by banning hospitals and academic institutions from promoting instant formula to families.[129] As a consequence, six Nestlé employees were given prison sentences between one and six years.[128]

Slavery and child labour

Multiple reports have documented the widespread use of child labour in cocoa production, as well as slavery and child trafficking, throughout West African plantations, on which Nestlé and other major chocolate companies rely.[130][131][132][133][134] According to the 2010 documentary, The Dark Side of Chocolate, the children working are typically 12 to 15 years old.[135] The Fair Labor Association has criticised Nestlé for not carrying out proper checks.[136]

In 2005, after the cocoa industry had not met the Harkin–Engel Protocol deadline for certifying that the worst forms of child labour (according to the International Labour Organization’s Convention 182) had been eliminated from cocoa production, the International Labor Rights Fund filed a lawsuit in 2005 under the Alien Tort Claims Act against Nestlé and others on behalf of three Malian children. The suit alleged the children were trafficked to Ivory Coast, forced into slavery, and experienced frequent beatings on a cocoa plantation.[137][138] In September 2010, the U.S. District Court for the Central District of California determined corporations cannot be held liable for violations of international law and dismissed the suit. The case was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals.[139][140] The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision.[141] In 2016, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Nestlé’s appeal of the Ninth Circuit’s decision.[142]

A 2016 study published in Fortune magazine concluded that approximately 2.1 million children in several West African countries «still do the dangerous and physically taxing work of harvesting cocoa», noting that «the average farmer in Ghana in the 2013–14 growing season made just 84¢ per day, and farmers in Ivory Coast a mere 50¢ […] well below the World Bank’s new $1.90 per day standard for extreme poverty». On efforts to reduce the issue, former secretary general of the Alliance of Cocoa Producing Countries, Sona Ebai, commented «Best-case scenario, we’re only doing 10% of what’s needed.»[143]

In 2019, Nestlé announced that they could not guarantee that their chocolate products were free from child slave labour, as they could trace only 49% of their purchasing back to the farm level. The Washington Post noted that the commitment taken in 2001 to eradicate such practices within four years had not been kept, neither at the due deadline of 2005, nor within the revised deadlines of 2008 and 2010, and that the result was not likely to be achieved for 2020 either.[144]

In 2021, Nestlé was named in a class action lawsuit filed by eight former child slaves from Mali who alleged that the company aided and abetted their enslavement on cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. The suit accused Nestlé (along with Barry Callebaut, Cargill, Mars Incorporated, Olam International, The Hershey Company, and Mondelez International) of knowingly engaging in forced labor, and the plaintiffs sought damages for unjust enrichment, negligent supervision, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.[145][146] The lawsuit was dismissed in June 2021 by the Supreme Court of the United States.[147][why?]

Food safety

Milk products and baby food

In late September 2008, the Hong Kong government found melamine in a Chinese-made Nestlé milk product. Six infants died from kidney damage, and a further 860 babies were hospitalised.[148][149] The Dairy Farm milk was made by Nestlé’s division in the Chinese coastal city Qingdao.[150] Nestlé affirmed that all its products were safe and were not made from milk adulterated with melamine. On 2 October 2008, the Taiwan Health ministry announced that six types of milk powders produced in China by Nestlé contained low-level traces of melamine, and were «removed from the shelves».[151]

As of 2013, Nestlé has implemented initiatives to prevent contamination and utilizes what it calls a «factory and farmers» model that eliminates the middleman. Farmers bring milk directly to a network of Nestlé-owned collection centers, where a computerized system samples, tests, and tags each batch of milk. To reduce further the risk of contamination at the source, the company provides farmers with continuous training and assistance in cow selection, feed quality, storage, and other areas.[152] In 2014, the company opened the Nestlé Food Safety Institute (NFSI) in Beijing that will help meet China’s growing demand for healthy and safe food, one of the top three concerns among Chinese consumers. The NFSI announced it would work closely with authorities to help provide a scientific foundation for food-safety policies and standards, with support to include early management of food-safety issues and collaboration with local universities, research institutes and government agencies on food-safety.[153]

In an incident in 2015, weevils and fungus were found in Cerelac baby food.[154][155][156]

Cookie dough

In June 2009, an outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 was linked to Nestlé’s refrigerated cookie dough originating in a plant in Danville, Virginia. In the US, it caused sickness in more than 50 people in 30 states, half of whom required hospitalisation. Following the outbreak, Nestlé voluntarily recalled 30,000 cases of the cookie dough. The cause was determined to be contaminated flour obtained from a raw material supplier. When operations resumed, the flour used was heat-treated to kill bacteria.[157]

Maggi noodles

In May 2015, food safety regulators from the state of Uttar Pradesh, India, found that samples of Nestlé India’s Maggi noodles had up to 17 times more than the permissible safe amount of lead, in addition to monosodium glutamate.[158][159][160] Due to this, on 3 June 2015, the New Delhi Government banned the sale of Maggi in New Delhi stores for 15 days.[161] Some of India’s biggest retailers, such as Future Group, Big Bazaar, Easyday, and Nilgiris, had imposed a nationwide ban on Maggi as of 3 June 2015.[162] On 4 June 2015, the Gujarat FD banned the sale of the noodles for 30 days after 27 out of 39 samples were detected with objectionable levels of metallic lead, among other things.[163] On 5 June 2015, Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) orders banned all nine approved variants of Maggi instant noodles from India, deeming them «unsafe and hazardous» for human consumption,[164] and Nepal indefinitely banned Maggi over concerns about lead levels in the product.[165] Maggi noodles have been withdrawn in five African nations – Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, and South Sudan – by a supermarket chain after a complaint by the Consumer Federation of Kenya, as a reaction to the ban in India.[166]

In India, Maggi products were returned to the shelves in November 2015,[167][168] accompanied by a Nestlé advertising campaign to win back consumer trust, featuring items such as[169] the Maggi anthem by Vir Das and Alien Chutney.[170] Nestlé resumed production of Maggi at all five plants in India on 30 November 2015.[171][172]

In the Philippines, localised versions of Maggi instant noodles were sold until 2011 when the product group was recalled for suspected salmonella contamination.[173][174] The product did not return to market, while Nestle continues to sell seasoning products including the popular Maggi Magic Sarap.[citation needed]

Water

Status of potable water

At the second World Water Forum in 2000, Nestlé and other corporations persuaded the World Water Council to change its statement so as to reduce access to drinking water from a «right» to a «need». Nestlé continues to take control of aquifers and bottle their water for profit.[175] Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, chairman of Nestlé, later changed his statement, saying in a 2013 interview, «I am the first one to say water is a human right.» In that same interview, he claimed that it was the «primary responsibility of every government» to provide 30 litres of water a day to citizens.[176]

Plastic bottles

A coalition of environmental groups filed a complaint against Nestlé to the Advertising Standards of Canada after Nestlé took out full-page advertisements in October 2008 with messages claiming, «Most water bottles avoid landfill sites and are recycled», «Nestlé Pure Life is a healthy, eco-friendly choice», and, «Bottled water is the most environmentally responsible consumer product in the world.»[177][178][179] A spokesperson from one of the environmental groups stated: «For Nestlé to claim that its bottled water product is environmentally superior to any other consumer product in the world is not supportable.»[177] In their 2008 Corporate Citizenship Report, Nestlé themselves stated that many of their bottles end up in the solid-waste stream, and that most of their bottles are not recycled.[178][180][181] The advertising campaign has been called greenwashing.[178][179][180] Nestlé defended its ads, saying that they will show they have been truthful in their campaign.[177]

Water bottling operations in California, Oregon and Michigan

Considerable controversy has surrounded Nestlé’s bottled water brand, Arrowhead, sourced from wells alongside a spring in Millard Canyon situated in a Native American Reservation at the base of the San Bernardino Mountains in California. While corporate officials and representatives of the governing Morongo tribe have asserted that the company, which started its operations in 2000, is providing meaningful jobs in the area and that the spring is sustaining current surface water flows, a number of local citizen groups and environmental action committees have started to question the amount of water drawn in the light of the ongoing drought, and the restrictions that have been placed on residential water use.[182] Additionally, recent[when?] evidence suggests that representatives of the Forest Service failed to follow through on a review process for Nestlé’s permit to draw water from the San Bernardino wells, which expired in 1988.[183][184] In San Bernardino, Nestlé pays the US Forest Service $524 yearly to pump and bottle about 30 million gallons, even during droughts. Peter Gleick, a co-founder of the Pacific Institute, which researches freshwater issues, remarked «Every gallon of water that is taken out of a natural system for bottled water is a gallon of water that doesn’t flow down a stream, that doesn’t support a natural ecosystem.» He also said, «Our public agencies have dropped the ball».[185]

The former forest supervisor Gene Zimmerman has explained that the review process was rigorous, and that the Forest Service «didn’t have the money or the budget or the staff» to follow through on the review of Nestlé’s long-expired permit.[186] However, Zimmerman’s observations and action have come under scrutiny for a number of reasons. Firstly, along with the natural resource manager for Nestlé, Larry Lawrence, Zimmerman is a board member for and played a vital role in the founding of the nonprofit Southern California Mountains Foundation, of which Nestlé is the most noteworthy and longtime donor.[187] Secondly, the Zimmerman Community Partnership Award – an award inspired by Zimmerman’s actions and efforts «to create a public/private partnership for resource development and community engagement» – was presented by the foundation to Nestlé’s Arrowhead Water division in 2013.[188] Finally, while Zimmerman retired from his former role in 2005, he currently works as a paid consultant for Nestlé, leading many investigative journalists to question Zimmerman’s allegiances prior to his retirement from the Forest Service.[186]